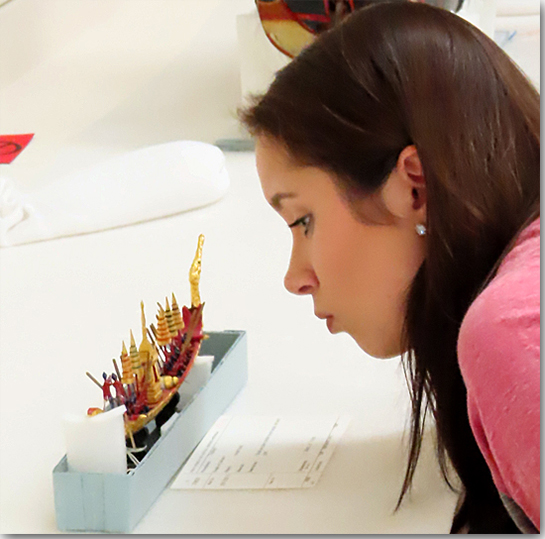

A student looks closely at the detail on a model boat from Thailand.

Introduction

How do you do fieldwork on a shipwreck when you aren't certified to scuba dive and don't even live near a large body of water? That was the question facing my Introduction to Maritime Archaeology class at Monmouth College, located in rural Illinois. Fortunately, while we may not have been able to access an actual shipwreck, we had the next best thing: access to Chicago's Field Museum, which houses an extensive collection of ship models. Many of these were accessioned by the museum after the World's Columbian Exposition (better known as the World's Fair) hosted by Chicago in 1893. Most had only minimal information associated with them, usually consisting of not much more than the geographic origin of the model.

Anthropology Collections Manager Jaime Kelly instructs the students in handling the ship models.

With the cooperation of the Field Museum, we treated these ship models as proxy shipwrecks.1 My class visited the museum where Head of Anthropological Collections Jaime Kelly kindly had arranged for us to get a closer look at some of the models. After a brief introduction to the museum's collections and protocol, the students perused a selected group of models that would become the focus of their semester-long project. Each would choose one to record and research over the coming months in a simulation of an archaeological project on an actual shipwreck site.

Each student needed to first record their model: taking measurements, drawing it, and recording any information from the museum's files about their boat. They were aware of the need to take photos both for their own use, but also images that would eventually be suitable for an online exhibit. We discussed the pitfalls of working with models as opposed to actual ships, as there was no guarantee that the model maker was working with accurate dimensions originally. Students needed to conduct their future research with those limitations in mind.

Students take notes and document their chosen models.

Over the course of the semester, they researched the ship construction represented in the models to find out more about the vessels themselves. They identified particular diagnostic features that suggested more information about where and when an actual boat represented by that model might have sailed. Later they went on to do more research about the seafaring culture associated with their vessel, trying to determine who might have sailed on their boat and why. This was meant to reproduce the research that would accompany an archaeological site, as once we've excavated a shipwreck we need to learn more about it.

The students' final task was the same as that of any archaeologist: to disseminate information about their work. They chose three images that best represented their particular ship model and, based on the information from their earlier research, wrote accompanying labels for this museum exhibit. We hope that this provides some information about our proxy shipwrecks for the general public.2

We would especially like to thank Jaime Kelly and the Field Museum for generously opening up their collections to us, and Dr. Kurt Knoerl and the MUA for making this exhibit possible.

- Dr. Michelle Damian

With great thanks to the Field Museum for their help!

1One student chose to do her project on an actual boat that she researched remotely, so this exhibit does not focus exclusively on the Field Museum collection.

2All information is in the students’ own words, and has not been endorsed by the Field Museum.

Next